Adolescent Wonderland

by Shonae Hobson

When you drive into Coen, a small community of 364 people, located in the heart of Cape York Peninsula, the first thing you see are the mountains, engulfed in thick bushland that leads into fresh streams of running river water. For my people, the Kaantju people, whose ancestral lands surround this area, this is our home. This is the place where my mother, her mother and her mother before her lived. Generations of kin have lived on this Country – their memories forever etched into the fabric of the surrounding landscapes.

Yet, despite these familiar surroundings, and underneath the community’s beautiful façade, a colonial history echoes through the town, telling us of our past and serving as a constant reminder of the hardships that our old people endured. Today, unbeknown to many visitors, there is the distinction between two graveyards – one for black people and the other for white. When you enter Coen, the graveyards are separated by a long stretch of bitumen road, and at the end of this stretch a sign reads ‘Welcome to Coen’.

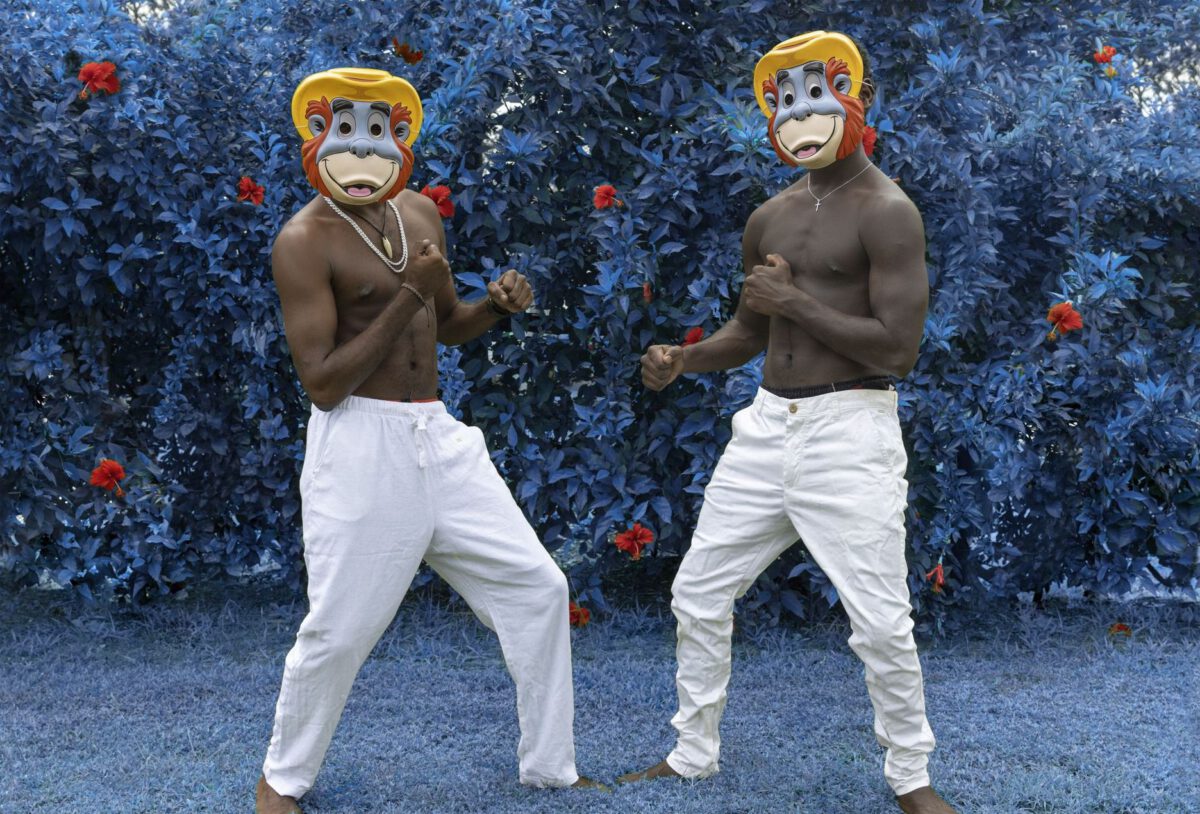

For my mother, Naomi Hobson, a multidisciplinary artist of Kaantju and Umpila descent, the colonial history of the township, and her interpretation of it through positive and uplifting imagery, is an integral part of her artistic practice. The outpouring of positive reaction to Hobson’s photographic series Adolescent Wonderland stands as testament to a body of work that is the gold standard in telling the real-life story of young Indigenous people in remote Australia. The title Adolescent Wonderland draws inspiration from the iconic fairytale novel of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Parallel themes of youth, playfulness and childhood memories resonate throughout Hobson’s photographs. Each of her subjects is carefully situated in a place and shown with props that invite the viewer into a dream-like reality. For instance, one work, Road Play, depicts sisters Laine and Katarna on a street outside their home and illustrates the dualities between teenage adolescence and childhood nostalgia. Laine is pictured wearing a white ‘rabbit’ mask – a clever reference to Alice’s escape into the rabbit hole that leads to a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatures and characters. The symbol of the rabbit is used as a metaphor for the playful and adventurous lifestyle of Indigenous kids today.

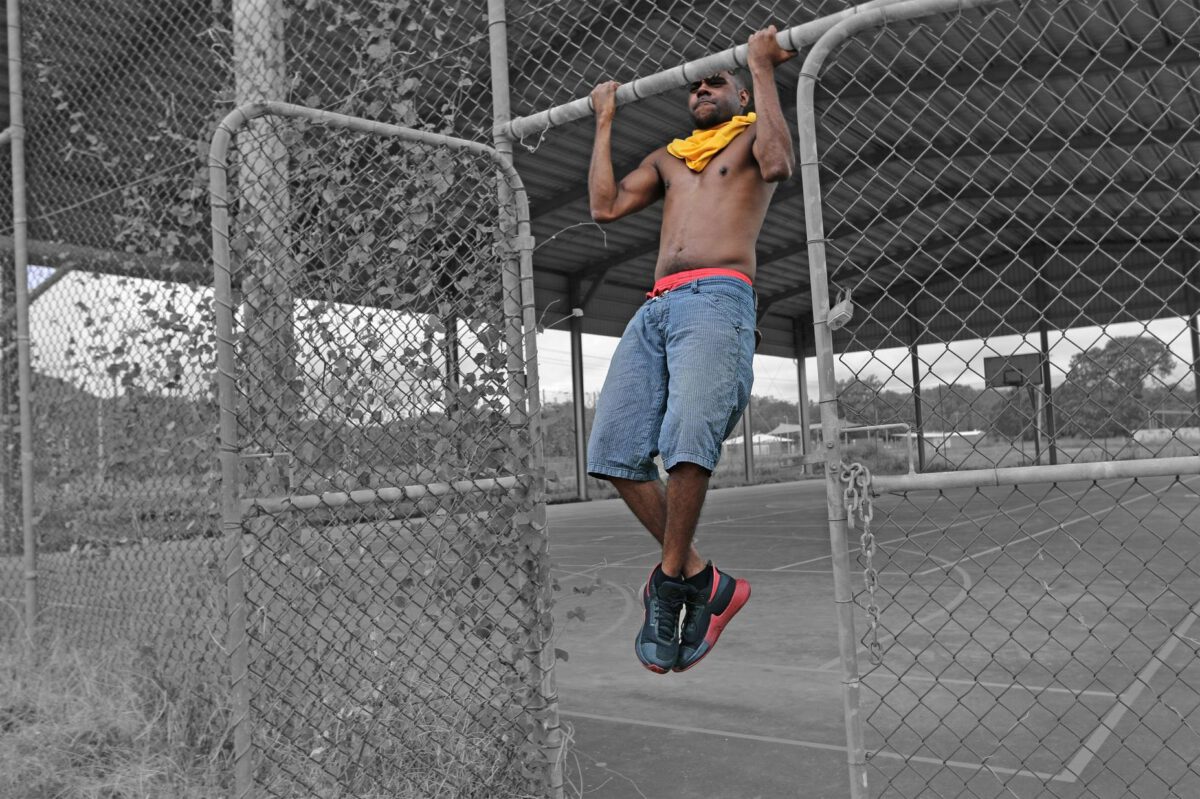

Offering a rare glimpse into the lives of young people in the township of Coen, Hobson allows the viewer to become part of the community. She captures the cheer, wittiness and optimism that is Indigenous community life today. Underneath the trauma and history that surrounds the town is a sense of confidence and hope for the future. Hobson says,

Today photography needs to push the boundary. I feel it doesn’t need to be picture perfect and as a fine art – I’m using the medium to tell real stories that I feel don’t get told or haven’t been told. I want people to see who our youth really are; fun, playful, smart, savvy, proud, adventurous and witty.

Hobson reframes the colonial narratives of Indigenous peoples as subjects of the white gaze. Her personal affiliation with the people whom she depicts stems from an ongoing relationship with them. She has watched the kids of today grow up and begin their journeys. She knows their stories intimately and translates those narratives into her photographs. It is a refreshing departure from the historical perspective of Indigenous life portrayed within the social sciences, and this is clearly appreciated by the people with whom the artist resides – self-evident from the confidence with which they discuss life and the narrative of the photographic projects.

I grew up in Coen and lived with the artist during her time working on the Adolescent Wonderland series in 2018. Mum would stop and chat with people as they would go about their daily life in the community, discussing what the young people were getting up to but always with inquiry and interest. She was always interested in their wellbeing and especially their future, she always spoke to them in a way that was encouraging – a way that cuts straight to a dialogue delving deeper into thought and analysis and often establishes a journey of mutual discovery. The engagement is reciprocated, and the expectation of the appearance of a camera is evident, enthusiastic and even sought after. What is clear is that Hobson is engaging with people about the photographs in a way that places far more emphasis on the story than the script followed by technical photography, while remaining acutely aware of how she wants each image to break down the stereotype of remote Indigenous Australians.

As audiences we are observing a journey that does not end with a photograph. Moreover, it is the beginning of an empowering process with an ongoing interaction, and a bubbling conversation in the community around the images and the integrity and honesty of their respective stories. The importance of Adolescent Wonderland should not be overlooked. There is a real ownership of the image as a story that will forever be seen and told, something to hand down or pass on.

An upsurge of interest in photography in Coen can be directly attributed to Hobson’s photographic series. Her imagery has provided an ongoing critique of negative public stereotypes of Indigenous people and mainstream perceptions of her people – characterisations that could not be further from the reality of life for Coen’s 300 residents. Hobson consistently reiterates,

We have our culture, but we’re also in touch with the world now. Our young people are confident, energetic and kind of up to date. Adolescent Wonderland is getting people to appreciate just being themselves.

Hobson’s photographs are a testament to her daring flair and credibility as an artist versed in a variety of mediums. Her photographs are both challenging and emotive; they transform how we as audiences engage with imagery. Through her photographs, Hobson provides a rare glimpse into the everyday experiences of youth from Coen. The calibre of her work has also established profound respect for her and for photography done right, and it has imbued a self-confidence in Coen’s people to share their voice and lived experiences in front of the lens.